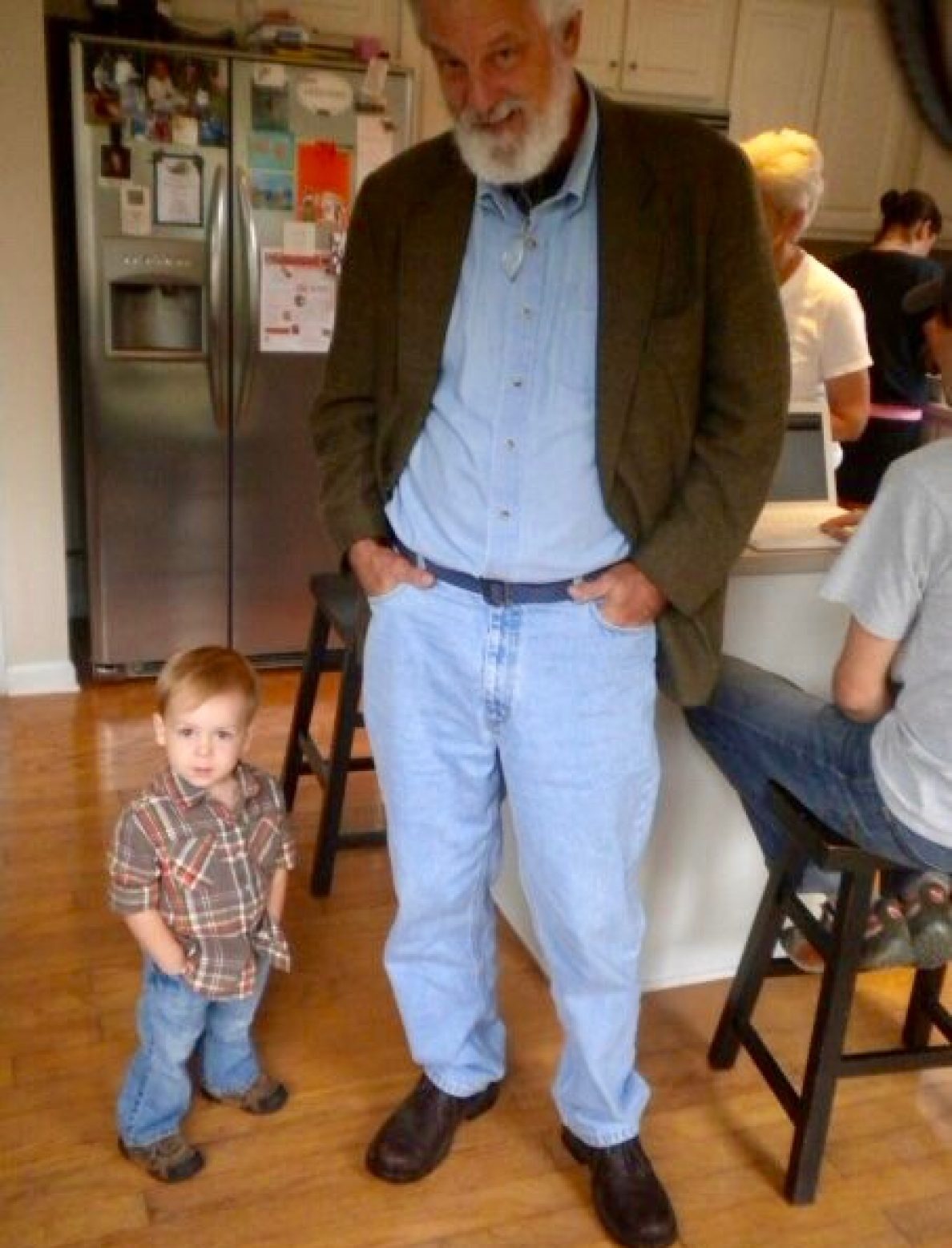

Fifty years ago, when I was graduating from the University of North Carolina, my hometown, Greensboro, was in turmoil. I was mostly oblivious to what was going on. Here’s a long article about an important part of US history.

Three days in May: A look back at the 1969 disturbances that rocked a college campus and a city

- By John Newsom john.newsom@greensboro.com

- 20 hrs ago

- 15 min to read

A portion of the exterior wall of Scott Hall that was shot up during the disturbance. The dorm was torn down in 2004. Portions of the wall are part of a reflecting pool at N.C. A&T in Greensboro, N.C., on Wednesday, May 9, 2019.

- Khadejeh Nikouyeh/News & Record

Greensboro police stand guard on the edge of the N.C. A&T campus on May 23, 1969. Cooper Hall, an A&T dormitory, stands in the background.

- News & Record

GREENSBORO — The 1960s started in the city when four black college students protested racial segregation by sitting down at a whites-only lunch counter.

It ended nine years later when hundreds of N.C. A&T students hid in their dorm rooms and tried not to get shot by the National Guard.

The events of May 21 to May 23, 1969, sparked by a disputed high school government election, rank among the darkest chapters in the city’s history.

Over those three long and bloody days 50 years ago, one student was fatally shot on the A&T campus, and eight other people were wounded by gunfire. Dozens more were hurt by debris hurled in anger and frustration. More than 300 people were arrested. National Guard troops shot up two A&T dorms.

The death of that A&T student, Willie Grimes, remains the city’s oldest unsolved homicide. A journalist writing for a New York newspaper shortly after those events called the National Guard deployment at A&T the largest armed assault ever seen against an American college campus.

Despite dominating the local and national headlines for a brief moment, the events of 1969 seem barely remembered except by those who survived the rocks and bullets.

Fifty years later, here is a look back at those turbulent times.

Prologue

Greensboro and college campuses across the country were no strangers to protests and violence during the 1960s.

For nearly three weeks in 1963, young black Greensboro residents filled the streets and then the jails to demand the integration of local restaurants, cafeterias and movie theaters. When the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated five years later, peaceful marches in Greensboro gave way to gunfire. Police and soldiers used tear gas to flush out snipers hiding in A&T buildings. Six people, including four Greensboro police officers and a National Guardsman, were wounded by bricks or shotgun blasts.

Also in 1968, students at Columbia and Howard universities occupied administration buildings. In February of that year, highway patrol troopers killed three and wounded 27 when they fired into a crowd at South Carolina State University, the historically black school in Orangeburg. Students there had been protesting a local bowling alley that refused to admit black customers.

In early 1969, several A&T students briefly took over the administration building to protest grading practices and their treatment by some professors. A student-supported cafeteria-workers strike that started at UNC-Chapel Hill in February spread to A&T and UNCG in March.

A protest at Duke University served as a template for what was to come at A&T. In 1968, when white students occupied the president’s house and then a campus quad, Duke leaders let the protest go on for eight days.

When black students took over the administration building a year later, police used tear gas to end the protest.

“What that suggests to me is that there was an attitude when dealing with black protesters,” said William Chase, a Duke University historian whose books include an overview of Greensboro during the Civil Rights era. “You didn’t have the same obstacles in front of you as you did with white students.”

May 1969

By May 1969, the spring semester was winding down at A&T, but nearby Dudley High School was nearing a crisis.

Dudley’s administration ran a tight ship, and some students wanted the rules to be loosened. They wanted to wear longer hair and jeans to school. They asked to be able to leave campus for lunch, something that students at other Greensboro high schools could do. They wanted classes on African American history and repairs made to their aging school buildings.

The main student leader was the junior class president, Claude Barnes, a popular athlete and honors student. Off campus, he belonged to Black Power groups and led youth efforts to fight for the rights of black people.

When Barnes decided to run for student body president, the school said no. They saw Barnes as a militant under the thumb of outside forces.

“That wasn’t true, of course,” Barnes, now a retired A&T professor, told the News & Record in 1999. “They (school administrators) believed anyone who wore black belonged to the Black Panther Party. I dressed in black, like a lot of black kids at that time.”

The election was held May 2. The candidate who got 200 votes was declared the winner. Barnes said later that 600 Dudley students wrote his name on their ballots.

After the election results were announced, Barnes and four other Dudley students walked out of the high school in protest and over to A&T. There, they sought help from an A&T junior who had just been elected student body vice president, an Air Force veteran named Nelson Johnson. The summer before, Johnson had started the Greensboro Association of Poor People to help black city residents fight for better housing and jobs and against racial discrimination. Barnes had been the group’s youth leader.

Later on May 2, Johnson went to Dudley to try to talk with the principal. But events were already starting to spiral out of control. The week after the election, the five students who had left campus were suspended, but later reinstated. Dozens and then hundreds of Dudley students walked out of class. A&T students joined the protest.

The Greensboro school district, meanwhile, sent its public relations director to Dudley to deal with reporters and advise the principal. Black leaders believed the all-white school board didn’t trust the principal of its all-black high school, so it sent in their own man to run things.

Community gatherings, city commissions, secret negotiations — nothing was working.

Johnson and two others were arrested May 13 and charged with interfering with the operations of a public school. Dudley students picketed their school.

On May 19, a Monday, 17 students were arrested and school let out early. The protests continued the next day.

Wednesday, May 21

Dudley High School opened at its usual time Wednesday morning. By 9:30 a.m., some students were picketing the school. Inside, community leaders tried to arrange a meeting so students could air their complaints.

By about 1:30 p.m., the ranks of protesters had grown to more than 100. Police and school officials asked them to leave. Students agreed to if police would withdraw, too. Students left. Officers left.

Fifteen minutes later, students ran back to campus and threw rocks that shattered some school windows. Officers returned in riot gear and with tear gas.

It was chaos.

The Dudley principal closed the school and told students to go home. Several hundred A&T students marched over from their campus. High school and college students threw rock and bottles at police and the school.

Some Dudley students tried to get back into the high school to escape the smoke and the police. Still others ran for home. People who lived near the school complained they couldn’t sit on their front porches because the gas was so thick. A woman fainted and was carried inside a nearby house.

“Talk about brutal,” one woman told the Greensboro Daily News. “Here (the police) come with their guns and their gas and their helmets and their billies. It was brutality if ever I saw it.”

The violence boiled over into the neighborhoods. Black youths threw rocks at police cars and vehicles driven by whites along McConnell Road and East Market Street. A local judge barred 40 people from Dudley’s campus or risk arrest. At least 15 people were reported hurt.

That night, Greensboro Mayor Jack Elam went on TV and declared, “We no longer have good order in our community.” He asked the governor to send in the N.C. National Guard. About 150 soldiers arrived in jeeps and armored vehicles to help police patrol the city.

As fires and shots were reported throughout the city, things were quiet at A&T, the state university of about 4,000 students. About 10 p.m., after a campuswide meeting, some students wandered over to The Block, the stretch of stores that once lined East Market Street near campus, and joined the crowd of other black youth watching the parade of police cars and military vehicles. People threw rocks and bottles. Police responded with tear gas and pepper spray.

There was gunfire police said had come from A&T buildings. Officers shot back. Male students seeking refuge crawled over to the nearby women’s dorms. The college ordered the women’s residence halls to be locked down, so the young men ran and crawled to their dorms on the north side of campus.

Things would only get worse.

Thursday, May 22

Thursday was only about an hour old when Willie Grimes was killed.

Grimes, an A&T sophomore, was fatally shot while walking from campus to a fast-food restaurant on Summit Avenue.

Almost immediately, many students and black city residents blamed Greensboro police for Grimes’ death. Police department leaders said neither their officers nor the National Guard used weapons that fired the single small-caliber bullet that killed Grimes. Students charged that some police officers had brought their own rifles from home.

An FBI agent based in Greensboro blamed Grimes’ death on a stray bullet. A Greensboro police detective told the News & Record in 2006: “It’s like he was a casualty of war.”

No one was arrested, much less tried, in connection with Grimes’ killing. Fifty years later, his death remains the city’s oldest unsolved homicide.

As Grimes lay dead in the hospital, the violence continued. Shooting, rock-throwing and small fires were reported all over the city, but the locus of much of the violence was the A&T campus.

Police said snipers were hiding in several A&T buildings, including W. Kerr Scott Hall, the 1,000-bed fortress of a dorm named for a former N.C. governor whose son was now governor. Police shot back. Officers also arrested nine people overnight for disorderly conduct and carrying concealed weapons.

At a 10 a.m. news conference, the mayor declared a state of emergency in Greensboro. A curfew would start at 8 that night and last until 5 the next morning. The city’s liquor stores would close. All marches and demonstrations would be banned. Anyone caught with weapons or explosives would be arrested.

As the mayor spoke, black youths stopped a linen truck near the A&T campus, dragged the white driver from behind the wheel, turned over the vehicle and set it on fire.

The university held classes as normal Thursday morning. By that afternoon, police had blocked all the roads leading into the college, and parts of the campus were off-limits to students.

About 4 p.m., A&T President Lewis Dowdy closed the school and canceled exams scheduled for the following week “in the interest of the safety of our students and members of the university community.” Dorms and dining halls would remain open until 6 p.m. Friday to give students a chance to pack up and get out without violating the city’s curfew. Dowdy canceled the next week’s exams and all campus activities except for commencement June 1.

The citywide curfew took effect at 8 p.m. In that first hour, police arrested eight people — seven blacks, one white — for violating that curfew.

On campus, it was a stalemate. Police ringed the campus. Students slept under their beds as they waited to go home. And shots rang out all over.

Friday, May 23

The worst was yet to come.

Around 1 a.m., five Greensboro police officers patrolling a dead-end street near campus were hit by pistol bullets and shotgun pellets. The wounded officers were pinned down by gunfire for about 10 minutes before two armored troop carriers could arrive. An A&T student was wounded in the exchange of gunfire. SKIP AD

Police called it an ambush. No one was arrested or charged in this assault.

As the sun rose, police retreated from campus and A&T students emerged from their dorms to get breakfast. A dining hall TV reported that National Guard soldiers were awaiting orders somewhere near campus.

Jessie James Jr., an A&T senior, knew those reports weren’t true. Outside the dining hall, he and other students watched as many of the 650 National Guard soldiers now in Greensboro marched down Bluford Street and past the Holland Bowl. A machine gunner took aim at Scott Hall.

“We were watching out the window, and there they were,” James, now a Virginia attorney, recalled earlier this month. “And they were shooting.”

Bullets thudded into the western wall of Scott Hall. As windows shattered, students dropped to the floor to avoid getting hit. A helicopter and airplane flying overhead dropped smoke and tear gas.

Ronald Harris, another A&T senior, remembers that soldiers held him and other students at gunpoint outside Brown Hall.

“I heard one of them say, ‘If anybody in this crowd moves a muscle, level them’ — that’s the word they used,” said Harris, a retired Atlanta school principal, said this month. “I’m lucky to be alive.”

At 6:45 a.m., the National Guard ordered students to leave both Scott and nearby Cooper Hall. Fifteen minutes later, soldiers started to clear the dorms, hall by hall, room by room.

Royall Mack, a senior and baseball team captain, told the News & Record in 2004 that after 20 minutes of gunfire, he remembers hearing the slap of boots on the tiled hall floors and soldiers shouting, “Stay down! Stay down!”

Soldiers in gas masks kicked in some doors and shot the locks off of others. Students emerged with their hands up, crying and vomiting from fear and gas. Soldiers looking for weapons turned over mattresses and broke open the students’ trunks, packed and locked for the trip home. It took the National Guard about four hours to clear out both dorms.

The only injury that day was to a National Guard sergeant, shot in the arm as he frisked a student. Police loaded about 300 students into prison buses to take them downtown for fingerprinting. Later that afternoon, they were all set free. The same buses brought students back to campus so they could go home.

That night, the military action at A&T made the national news. TV cameras caught Army trucks and armored vehicles rolling through Greensboro, soldiers with helmets and rifles charging across the A&T campus and students being frisked outside their dorms. An NBC reporter called it an “invasion.”

The next morning, the curfew and state of emergency were lifted, and the National Guard began to leave town. “Good order,” Mayor Jack Elam declared, “has been restored in our city.”

The shooting had ended. The shouting would continue.

Aftermath

Three days of violence came with a heavy toll. One A&T student was dead, and eight others — two students, five police officers and a National Guard soldier — had been wounded by gunfire. Rocks, bricks and bottles had hurt dozens more and damaged vehicles and buildings throughout Greensboro.

The A&T campus was in shambles. There were at least 50 bullet holes in the western wall of Scott Hall. Those holes remained until A&T razed the dorm in 2004.

Inside Scott and Cooper halls, furniture had been turned over, and clothing, books, radios and other belongings were scattered and damaged. Many rooms were covered in broken glass and a fine plaster dust. There were bullet holes in the windows, bullet holes in the doors, bullet holes in the windows. The entire campus stank of tear gas.

Students complained of missing belongings — money, watches, radios, class rings. (The National Guard commander denied that his soldiers looted the dorms.) A&T estimated the damage to its dorms at nearly $57,000 — almost $400,000 today.

To this day, it’s unclear who shot at authorities and with what.

Police said they found booby traps — bottles full of acid dangling from trees around campus — and seized about 10 rifles from Scott Hall. But only three of those guns actually worked. The rest had lead plugs in their barrels and appeared to be replicas used by student ROTC members in drills and parades. An informant had told police that students had stockpiled handguns, rifles and ammunition in Scott Hall. Rumors persist that before the National Guard assault, this arsenal was smuggled from the dorms through the steam tunnels that run underneath campus.

City leaders described the shooters as “snipers” and “militant students.” A documentary film and other witnesses tell how black Vietnam veterans — trained, armed and radicalized by their wartime experience — shot back at police and National Guard troops because they believed they were defending their campus from white authorities. Some of these former soldiers were A&T students. Others were veterans who came to campus to help. No one was ever charged with shooting at police or soldiers.

The finger-pointing continued long after the gunfire stopped.

On May 23, Gov. Robert Scott said the use of force was justified: “This was not a case of overreaction,” the governor told reporters in Greensboro. “Anytime you have officers wounded … you must face up to the responsibility to use the facilities at your command.”

Chafe, the Duke historian in his book “Civilities and Civil Rights,” called the armed assault of campus an overreaction. The official actions over these three days in May, he wrote, “all suggest the absence of a sense of balance.”

A&T held commencement on June 1 as scheduled in Moore Gymnasium on campus. The local newspapers reported that there were “a record 530 graduates.” But many of the graduating class didn’t return to campus once they left early the month before.

The next month, Greensboro’s police chief, A&T’s president and two others testified in Washington, D.C., before a Congressional subcommittee that was looking into campus disturbances. In 20 pages of testimony, the police chief held responsible lots of people — militants, Black Panthers, Nelson Johnson and especially outsiders for May’s racial unrest.

A short report compiled in 1970 for the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights also ladled out plenty of blame: on public school officials who didn’t take seriously the concerns of Dudley students; on white city and school officials who made key decisions without consulting the black leaders at both Dudley and A&T; on the city’s traditional black leadership for doing little to influence events; on police and the National Guard for using too much force and way too much tear gas.

“It is difficult to justify the lawlessness and the disorder in which this operation was executed,” the report said about the National Guard’s assault on A&T.

A decade later, former mayor Jack Elam called the committee’s report a “joke.”

Only two people were convicted of crimes related to the events of May 1969. One was Nelson Johnson, now a local minister and longtime community and civil rights leader. Johnson and another Greensboro man were sentenced to six months in prison for disrupting classes at Dudley High School. They served about a month in 1971 before Gov. Robert Scott commuted their sentences.

Fifty years later, Johnson sees May 1969 as the result of years of frustration. All of black Greensboro — its colleges, its churches, its businesses, its residents, the NAACP — was working together to fight segregation and oppression in the waning days of the Jim Crow South. White Greensboro, Johnson said — by denying Claude Barnes his presidency and sending in the police and National Guard — struck back at that unified front.

“I think to tell the truth about this story is to indict the culture that produced it,” Johnson said last week. “It was a revolt against the domination undergirded by white supremacy.”

May 2019

Fifty years later, only a few people seem to know the whole story of what happened on May 1969. But that might be changing.

Soon after Dudley and A&T returned to what passed for normal in 1969, other events grabbed the headlines. A year later, National Guardsmen killed four college students when they fired into an anti-war protest at Kent State University in Ohio. And Greensboro residents turned their attention to the complicated business of desegregating the city’s public schools.

The A&T students who lived through those three turbulent days remember those events vividly. But current and recent A&T students, meanwhile, seem to know little about those days.

Filmmaker Michael Anthony said he knew nothing of the story until he happened upon someone cleaning a campus marker dedicated to Willie Grimes. That chance encounter spurred Anthony, an A&T alum, to put together a documentary, “Walls That Bleed,” about the events of May 1969.

There are only a couple of clues on the A&T campus as to what happened there in 1969. One is the Grimes monument that now stands near a memorial to Aggies killed in foreign wars. It lists the date of Grimes’ death and says only that his “life was taken while struggling for true freedom.”

The other is a portion of the bullet wall, preserved when Scott Hall was torn down in 2004 and replaced by a more modern dorm complex. Four bullet-scarred sections of that brick wall now stand sentinel on each corner of a reflection pool at the former site of Scott Hall. A plaque on each monolith gives a short history of A&T. One of those plaques mentions riots, Grimes’ death and the National Guard.

“The bullet holes, still lodged in the walls,” it reads in part, “are a piercing reminder of those turbulent times.”

At commencement every year, A&T celebrates the class that graduated 50 years earlier. This year’s honorees were the class of 1969, many of whom missed out on their commencement.

For this class, A&T produced and played a 5-minute video at commencement that told the story of that unforgettable spring of 50 years ago. In that short film, three members of the class of 1969 shared their memories of bullets, tear gas and terror.

“We certainly cannot turn back the hands of time. We cannot unshoot the bullet that carried (away) Willie Grimes’ life,” Chancellor Harold Martin told the commencement audience after the film played.

“We cannot undo the terror of our students, faculty and staff and what they felt as armed National Guardsmen swarmed campus and opened fire on Scott Hall, or undo the … detention of 300 A&T students who spent that day in jails and prisons.

“What we can do — what is our honor to do today — is to celebrate the students who persevered through that period of chaos and violence. What we can do is recognize the productive, successful lives that so many went on to live. …

“What we can do is recognize the injustice that so many of them suffered in 1969 and not being able to have a proper graduation to celebrate their academic accomplishments.”

More than 100 members of the class of 1969 shared the arena floor of the Greensboro Coliseum with this year’s graduates. As the audience clapped and cheered, the 1969 graduates stood tall and waved — “brave men and women,” Martin said, “who faced down injustice at a cost to each of them.”

A&T May 1969 National Guard

A&T student hands up

A&T May 1969 Scott Hall

A&T National Guard Cooper Hall

A&T May 1969 students outside

A&T May 1969 National Guard

A&T National Guard on campus

A&T May 1969 student in dorm

A&T May 1969 students detained

A&T May 1969 National Guard

A&T May 1969 Scott Hall

A&T May 1969 Scott Hall

A&T May 1969 Greensboro police

NC A&T 1969 graduation

| Get today’s top stories right in your inbox. Sign up for our daily morning newsletter. |

Contact John Newsom at (336) 373-7312 and follow @JohnNewsomNR on Twitter.

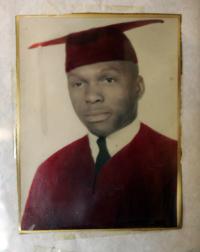

Profile: Willie Grimes, 1949-1969

The N.C. A&T sophomore was the lone fatality during the three days of violence in Greensboro in May 1969.

SOURCES

A glance at the sources used to produce this story:

• Newspaper accounts from May 1969 and thereafter in the Greensboro Daily News and the Greensboro Record, plus News & Record stories about Claude Barnes (1999), the Scott Hall dormitory (2004) and Willie Grimes (2006)

• “Trouble in Greensboro: A Report of an Open Meeting Concerning the Disturbances at Dudley High School and North Carolina A&T State University,” by the North Carolina State Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights (1970)

• “Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina and the Black Struggle for Freedom,” by William H. Chafe (1980)

• “Walls that Bleed: The Story of the Dudley/A&T Uprising,” a documentary film directed by Michael Anthony (2008; revised in 2012)

• “The Black Revolution on Campus,” by Martha Biondi (2012)

• Interviews by News & Record staff writer John Newsom in April and May 2019

More online

See related video with the digital version of this article at greensboro.com.